Video:

Bloggin internal news

There are seven key stages in a startup’s evolution from $0m to $50m in revenue. Understanding where you are in that evolution, and how to act at each stage is critical for success, as what is appropriate at one stage is not appropriate at another stage. In my talk at SaaStr 2018, I will lay out the roadmap, and detail the keys to success at each stage. The talk is aimed at technical/product founders plus their sales, marketing & product executives who are responsible for the go-to-market strategy for their company.

https://www.forentrepreneurs.com/saastr-2018/

“We’ve learned and struggled for a few years here figuring out how to make a decent phone. PC guys are not going to just figure this out. They’re not going to just walk in.” – Ed Colligan, CEO of Palm, 2006, on rumours of an Apple phone

“They laughed at Columbus and they laughed at the Wright brothers. But they also laughed at Bozo the Clown.” – Carl Sagan

When Nokia people looked at the first iPhone, they saw a not-great phone with some cool features that they were going to build too, being produced at a small fraction of the volumes they were selling. They shrugged. “No 3G, and just look at the camera!”

When many car company people look at a Tesla, they see a not-great car with some cool features that they’re going to build too, being produced at a small fraction of the volumes they’re selling. “Look at the fit and finish, and the panel gaps, and the tent!”

The Nokia people were terribly, terribly wrong. Are the car people wrong? We hear that a Tesla is ‘the new iPhone’ – what would that mean?

This is partly a question about Tesla, but it’s more interesting as a way to think about what happens when ‘software eats the world’ in general, and when tech moves into new industries. How do we think about whether something is disruptive? If it is, who exactly gets disrupted? And does that disruption that mean one company wins in the new world? Which one?

The idea of ‘disruption’ is that a new concept changes the basis of competition in an industry. At the beginning, either the new thing itself or the companies bringing it (or both) tend to be bad at the things the incumbents value, and get laughed at, but they learn those things. Conversely, the incumbents either dismiss the new thing as pointless or presume they’ll easily be able to add it (or both), but they’re wrong. Apple brought software and learnt phones, whereas Nokia had great phones but could not learn software.

However, not every new technology or idea is disruptive. Some things do not change the basis of competition enough, and for some things the incumbents are able to learn and absorb the new concept instead (these are not quite the same thing). Clay Christensen calls this ‘sustaining innovation’ as opposed to ‘disruptive’ innovation.

By extension, any new technology is probably disruptive to someone, at some part of the value chain. The iPhone disrupted the handset business, but has not disrupted the cellular network operators at all, though many people were convinced that it would. For all that’s changed, the same companies still have the same business model and the same customers that they did in 2006. Online flight booking doesn’t disrupt airlines much, but it was hugely disruptive to travel agents. Online booking (for the sake of argument) was sustaining innovation for airlines and disruptive innovation for travel agents.

Many initial coin offerings (ICOs) were tickets to quick riches in 2017. Take a token called Status—it was issued in June, raised about $100 million and soared 1,200% within six months. It’s easy to get excited by crypto’s surging prices. But now that the market has corrected somewhat and it’s clear that tokens both rise and fall, it’s prudent to determine whether the virtual asset you’re buying has merit and utility in the real world.

1. Who’s the team behind the coin?

Much like the venture capital world, the founding can make or break a crypto asset. When evaluating a coin’s developers, look beyond education to find out what projects they’ve built, says bitcoin investor and researcher Tuur Demeester. He likes to see that developers are “respected in the fields of cryptography, memory compression, peer-to-peer networks and large open-source projects.” The more knowledge and experience they have, the less likely they’ll be to repeat past mistakes that have plagued other crypto coins.

And try to evaluate the team’s integrity. Chris Burniske, co-author of the book “Cryptoassets”and a partner at crypto investment firm Placeholder Ventures, tells Forbes it’s important to “get to know the developers. If not in person, through podcasts, videos or talks.” Do they explain their project clearly, or do they seem evasive when answering questions? Do their motivations seem sound?

2. Read the white paper and ask what problem the coin is trying to solve

Developers typically publish a white paper that explains the software and economics behind a coin, and investors should read it with a critical eye. Cryptocurrencies’ main reason for existence is decentralization—they’re controlled by many people instead of a single, central authority. In crypto theory, that’s good because central authorities are more susceptible to incompetence and corruption. The white paper should clearly explain why the digital asset benefits from decentralization, Chris Burniske and Jack Tatar write in “Cryptoassets.”

Over the past five years, we’ve witnessed an Atomization of the Seed Stage. Early fundraising is no longer a one-and-done fundraise of a single round of Seed capital subsequently followed by a Series A 12–18 months later.

Rather, it has been broken into bits of a series of capital raises to reach meaningful milestones… “pre-seed,” “post-seed,” and rounds in between have become the norm. A seed extension has ceased to be the equivalent of scarlet letter, and instead has become commonplace.

Whether or not this situation is good or bad for entrepreneurs and the ecosystem, it is indeed reality.

One of the results of this change is that Founders now approach Series A funds with increasingly varied histories.

The flood of seed-funded companies coupled with proliferation of seed fundswilling to underwrite incremental capital into new and existing portfolio companies, has yielded a broad backlog set of “seed startups” with wild variations across the following three dimensions:

1. How much time has elapsed since company founding.

2. How much total capital has been put into the company since founding.

3. (Effective) post-money valuation.

Once upon a time there was a “bar” for Series A — a threshold, once crossed would yield a positive successful fundraise (e.g. $100K in MRR was cited).

https://bettereveryday.vc/seed-stage-startups-are-now-graded-on-a-curve-15a4968e8534

With plenty of resources available for entrepreneurs about how to craft an effective pitch deck for raising seed-stage capital from VCs, often what’s left out are some of the tactical components of an initial meeting.

The following is a list of mistakes that, despite seeming obvious or perhaps mundane, are still frequently committed by founders and CEOs. The good news? They’re easy to fix.

Every single pitch should, but unfortunately often don’t, contain specific,

…..

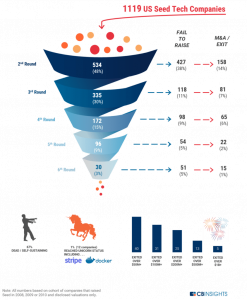

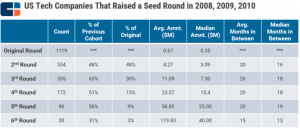

The venture capital funnel highlights the natural selection inherent in the venture capital process.

We followed a cohort of over 1,100 startups from the moment they raised their first seed investment to see what happens to them empirically.

So, once you take your first bit of seed funding, what can startup founders expect? The data bears out the conventional wisdom: nearly 67% of startups stall at some point in the VC process and fail to exit or raise follow-on funding.

In our latest analysis, we tracked over 1,100 tech companies that raised seed rounds in the US in 2008-2010. Less than half, or 48%, managed to raise a second round of funding. Every round sees fewer companies advance toward new infusions of capital and (hopefully) larger outcomes. Only 15% of our companies went on to raise a fourth round of funding, which typically corresponds to a Series C round.

The data below gives a more detailed look at the outcomes.

What we found:

Some other metrics:

Methodology:

……

Sam Altman, President of Y Combinator, shares his thoughts on how you can succeed with a startup.

Learn more at https://www.startupschool.org/

The following is an edited excerpt from Peter Thiel’s Zero To One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future. The excerpt was provided by Currency Publishing. You can buy a copy here.

Brand, scale, network effects, and technology in some combination define a monopoly; but to get them to work, you need to choose your market carefully and expand deliberately.

Every startup is small at the start. Every monopoly dominates a large share of its market. Therefore, every startup should start with a very small market. Always err on the side of starting too small. The reason is simple: it’s easier to dominate a small market than a large one.

https://www.techinasia.com/3-steps-building-monopoly-peter-thiel